Studying in the Learning Stages: A Guide for Students

In our first article, we introduced the Learning Stages, explaining that they describe how you learn (how you learn a subject that you are studying), as a process. They describe how you learn whether or not you understand the process, whether you pay attention to it or not.

But by understanding the process, and paying attention to the process, you can treat it like a procedure. You can make it more efficient. You can make it more effective. This article explains how to do that. It is organized in six sections:

- Review of The Learning Stages

- How Teaching is Organized

- Studying in LS1 (Introduction)

- Studying in LS2 (Absorption)

- Studying in LS3 (Application)

- Summary/Conclusion

1. Review of The Learning Stages

It is best to understand the Learning Stages in full, before you read this article, and before you try to apply the stages in your own studies. (Seriously. That introduction builds the intuitive foundation for understanding the stages themselves, as well as for understanding why you should invest the time and effort into learning the process that I describe here.)

To recap, learning is a process that progresses through three stages:

- LS1: Introduction - Initial exposure to the subject's concepts

- LS2: Absorption - Internalizing the concepts (and their details)

- LS3: Application - Using the concepts to solve problems

Your understanding of a subject develops (deepens) as you advance through these stages. It develops through study, and by completing tasks of increasing complexity and sophistication.

As you progress through these stages, you develop a Knowledge Model, in your long-term memory (LTM). This Knowledge Model represents your understanding - it is your understanding - of the concepts (and details) that you learned.

2. How Teaching is Organized

When you set out to learn a subject, you do so from one or more instructional sources. A textbook is an instructional source. So is a set of lectures - whether they are delivered to you live, in a classroom, or you view them as recorded videos. These are what you are taught from.

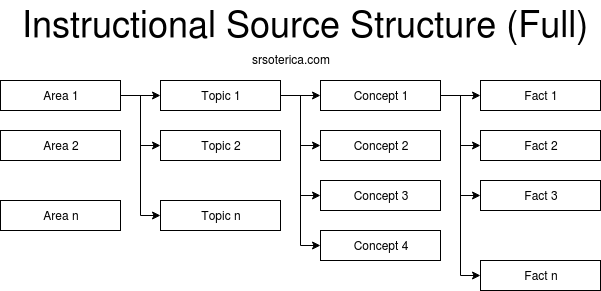

It is absolutely essential to understand that each instructional source has a structure in which the content is organized and delivered.

For example, a textbook is organized as a series of chapters. Each of the chapters is organized as a series of sections. Each of the sections introduces one or more concepts.

subject -> chapters -> sections -> concepts

These are not random groupings and divisions of the content. Though chapters and sections are usually numbered, they also have titles which (very briefly) describe what each chapter or section is going to talk about. Each section ends when its concepts have been adequately described. Each chapter ends when there are no more sections that need to be covered.

So chapters and sections are logical groupings of the subject's content. We can refer to the chapters as the major areas of interest in the overall subject. We can similarly refer to the sections as the major topics of interest within an area. With these generalizations, our structure looks like this:

subject -> areas -> topics -> concepts

(Referring to this structure as areas and topics allows us to talk more generally about instructional sources, since books have chapters and sections, but lectures, for example, do not.)

This structure is relatively easy to see in a textbook. It is harder to see the structure in lectures or videos. It is there, but you will have to suss out and keep track of the areas and topics on your own.

3. Studying in LS1 (Introduction)

LS1 begins at your first exposure to new instruction, and it continues until you can honestly say to yourself that you understand what you have read or viewed.

If your primary instructional source is a book, LS1 is about reading (and re-reading, as necessary) until you gain enough comfort with the material to move on to LS2. If your primary instructional source is lectures, LS1 is about viewing (and re-viewing, if possible).

It may take a substantial amount of time and effort to gain comfort with the new material. This is largely a factor of how well prepared you were (how well you performed in prerequisite subjects), and how well you study. But sometimes the subject is just inherently challenging. For example, in an advanced math class it is said that it can take an hour to understand a single page of the textbook.

Strategy

You can learn more efficiently in LS1 by focusing on the structure of the content as soon as possible.

The key to moving through this faster is to work at the right level of the content. You cannot understand a whole area (chapter), or even a whole topic (section), at once. Instead, you are trying to understand each of the concepts individually, one by one.

So you should look at studying in LS1 as a pipeline, preparing concepts for LS2:

- identify the next concept

- understand the concept

- take the concept to LS2

The earlier that you identify the concepts (within a topic), the earlier that you can understand each one individually. Once you understand an indivdual concept (and process it in LS2), you can start on understanding the next concept.

As you come to understand all of the concepts within a topic (section), you move on to the next topic and repeat the process, understanding each of the new topic's concepts, one by one. At some point you will finish all of the topics within an area (chapter), after which you will move on to the next area.

4. Studying in LS2 (Absorption)

There is a huge difference between being able to understand someone else's description of a concept, and being able to describe that concept yourself - from memory. That is the goal for LS2 - getting to that deeper level of understanding.

In order to be able to describe a concept yourself (from memory), you need to internalize your understanding of it - you need to construct a Knowledge Model representing the concept. You do so in a subprocess that I refer to as Absorption, because you absorb the concept into your memory, in a manner analogous to absorbing nourishment from food.

This subprocess has three substages - Decomposition, Memorization, Integration.

Decomposition is about breaking a concept down into individual, discrete facts. Then you Memorize those facts. After that, you Integrate the memorized facts into a holistic understanding of the concept.

It is important to remember that LS2 is fundamentally different than LS1 and LS3. Your teachers - and most instructional sources - are there to help when you need it in LS1 and LS3. But they are not there to help with LS2. You are entirely on your own in absorbing concepts into your long-term memory.

Decomposition

A concept (as described in your textbook, lecture, etc) is composed of, it is built up from, a set of facts that define the concept.

As we saw earlier, concepts are the parts of a topic, and topics are the parts of an area. Putting this all together, we can see that the complete structure of a subject looks like this:

subject -> areas -> topics -> concepts -> facts

Decomposition is about teasing the individual, discrete facts back out from a concept's description (in the textbook, lecture, etc). The reason that you have to do this is because a fact is the largest chunk size that you can memorize at once. Facts are the input to the Memorization substage in the same way that concepts are the input to Absorption (LS2) as a whole.

Strategy

Decomposition isn't difficult in terms of intellectual challenge (assuming that you understand the concept before you attempt to absorb it). But it's really easy to screw it up. You have to take care to do it correctly.

Your two goals here are simplicity and comprehensiveness.

Each individual fact has to be simple enough to fit in a single short sentence. If your "fact" is comprised of multiple sentences, you have not broken it down far enough yet. If your "fact" has commas in it, you might not have broken it down far enough yet.

If you fail to make the facts simple enough, you will not be able to memorize them. I cannot overemphasize this point. It is not a matter of being more, or less, difficult. You simply will not be able to remember them in a usable way if they are not easily stated.

In addition to simplicity, you must be comprehensive in breaking the concept down. Trivially, this means that you must not accidentally (or intentionally) skip over any of the concept's facts.

But you must also understand that there are simple facts, and there are higher-order facts. Higher-order facts include facts about (other) facts, as well as facts that relate the concept to other concepts, topics, or areas.

For example, "Addition is an arithmetic operation" is a simple fact. "Multiplication is an arithmetic operation" is also a simple fact. "Multiplication is repeated addition" is a higher-order fact - it relates one concept (arithmetic operation, in this case) to another.

If you fail to comprehensively decompose a concept, you will have much more difficulty integrating the concept (LS2 substage 3). If you skipped/missed enough of the facts - especially the higher-order facts - you might entirely fail to achieve Integration.

(Note that comprehensively decomposing a concept also strengthens the initial understanding of the concept that you developed in LS1. This is so because decomposing forces you to think about the concept and its facts, rather than just rereading their description.)

A set of facts typically starts as written notes - notes that you began writing in LS1, in order to keep track of the areas and topics, as well as the concepts. When you have completely decomposed the concept, you can move its set of facts (as a whole) to the next substage - Memorization.

Memorization

Memorization, the second substage of Absorption, is purely - entirely - a mechanical process. It is a process of repetition, repeated exposure to the individual facts that you decomposed from the concept's description in the instructional source.

You can memorize a set of facts by brute force, simply by viewing/reading each fact many times. If you choose to do so, your success or failure depends entirely on the count of repetitions, how many times you were exposed to each fact.

For hundreds - thousands - of years, students of all ages memorized entire subjects in this way. They did so because it worked, and because they lacked the tools to do it more effectively.

Strategy

Within the last few decades, we have learned that there are ways to make the Memorization process more efficient, and more effective. The most important ways to do this include exploiting the Testing Effect and the Spacing Effect.

These three factors - repetition, testing, spacing - together serve as the foundation for Spaced Repetition System (SRS) software. This technology only became feasible with the widespread availability of computers to students. SRS has since been proven to be the most effective way to learn in LS2.

Dozens of SRS platforms have become available over the last 30 years, many of which are free. All that you have to do is load your set of facts1 into the system, and start practicing. It will take days or weeks for the facts to solidify in your long-term memory (LTM), but it only takes a few minutes to review them each day. Trust the process.

Integration

Integration, the final substage of Absorption, is a process in which you develop a holistic understanding of a concept from the set of facts that you memorized. An integrated concept is one that you can describe, from memory, in a complete (and coherent) way.

The crucial thing to understand about Integration is that it is mostly a subconscious process. Which means that it is mostly not within your control. You can't predict the outcome of the process, or how long it will take to happen.

If you skipped memorizing important facts about a concept, you will have to rely on them forming naturally, in your mind, as "flashes of insight". These flashes arise seemingly randomly, and they may not occur until long after you have understood the concept (LS1), and memorized (some of) its facts.

This is why comprehensively decomposing a concept is so important. It is especially important to identify (and memorize) the higher-order facts. It is typically these higher-order facts that are not integrated until they appear later, as flashes of insight. Identifying and memorizing them - from the outset - places you that much further along in your overall understanding.

Strategy

You can encourage, and accelerate, Integration by actively contemplating the concepts that you have understood and memorized. Some of the ways to do this include:

- Try to recall a concept's facts (summon them from LTM into your working memory)

- Ask yourself questions about the concept, or about the facts that describe it

- Reflect on the concept as a whole, as the sum (or interaction) of its parts and behaviors

- Consider how the concept relates to, or compares to, other concepts

- Think about applications of the concept, or where else (in what subjects) it might be found

- Ponder the structure in which the concept fits. What topic is it a part of? What area?

These may not generate new insights immediately. But they will shape your subconscious thought processes in the intermediate to long terms, where a substantial portion of Integration happens.

They can also spur you to seek more information on the web, or in a book, or from some other instructional source. This, too, will refine your understanding. In fact, you may notice a snowball effect, as new facts are much more quickly and easily absorbed for concepts that you understand well, than for concepts that you are first coming to grips with.

When you can describe these things, from memory, and answer questions about the concept, you have integrated the concept. (More precisely, you have attained some degree of integrating the concept. Integration continues to happen as you go through LS32.)

There are tools and study techniques that can assist you with some of these activities. I will discuss some of these in future articles.

Revisiting the Concept Pipeline

I described LS1 as a pipeline, preparing concepts for LS2. We can extend this idea, so that here, at the end of LS2, the pipeline looks like this:

Pipeline steps/stages (through LS2):

| Learning Stage | Pipeline Step |

|---|---|

| LS1 | 1 - Identify the next concept |

| LS1 | 2 - Understand the concept |

| LS2 | 3 - Decompose the concept into a set of facts |

| LS2 | 4 - Memorize the set of facts |

| LS2 | 5 - Integrate the memorized facts into a holistic concept |

Once you have begun step 4 for a concept, you can go back to step 1 (LS1) to begin the process for the next concept. (Steps 4 and 5 take several days to complete. So there isn't really an alternative to starting the next concept anyway.)

Thus, you can visualize the learning of a subject as a series of concept pipelines staggered over time:

5. Studying in LS3 (Application)

LS3 includes an uncountable variety of possible tasks. Papers, projects, labs, case studies... These are just the categories in which we group and describe the tasks. The LS3 experience will be completely different from one subject to another, and even from one teacher to another.

As such, the advice that I give you about how to study here must be fairly general. That does not make it any less useful.

But first I need to highlight a couple of points that absolutely must shape your perspective in LS3.

First, if you did a good job in LS2, your experience in LS3 will be vastly easier. If you decomposed, memorized and integrated all of the concepts and their facts, you will be able to apply them much more quickly, easily and confidently, in your LS3 tasks. Phrased another way, a large percentage of your difficulties/struggles with LS3 tasks stem from not understanding the concepts well enough.

Second, you must also understand that all of these tasks - even quizzes and tests - are at least as much about helping you learn, as they are about forcing you to prove that you learned. They are designed to teach you how to use the concepts that you learned in LS1 and LS2. They are instructional sources, as well as being evaluation resources.

(If you doubt this, reread what I wrote above about ways to encourage Integration. How many of those activities resemble what you are asked to do on a test or a paper? Tests (in LS3) are forcing you to do the same thing that I am urging you to do in LS2. If you do it beforehand, in LS2, you will have much more time to do it, and you will be under little to no pressure when doing it.)

So think about these tasks as aids in your learning, rather than as obstacles to be feared and overcome. I know that that is easier said, than done. But it is nevertheless true.

Strategy

The closest thing to a strategy that I can give you for LS3 is this: start your papers/projects/etc as soon as they are assigned. I am not telling you this to warn you about the evils of procrastination, or the perils of last minute problems. Those are real concerns. But they are secondary concerns.

The reason why you should start early is to get your subconscious thinking about the task - about how to solve it - as early as possible.

You have undoubtedly had situations in life where the solution to a problem came to mind seemingly out of nowhere. You may have been taking a walk, or a shower, or watching TV.

This isn't magic, or Jung's collective unconscious, or any other such thing. It's how your mind, your long term thought process, works. Oakley calls it Diffuse Mode Thinking. Kahnemann calls it System 2 thinking. It is essentially the same as the Integration process that you go through (in LS2) in developing a holistic understanding from a set of discrete facts.

The process takes time, and it requires at least a basic understanding of the problem's details. So you should start thinking about the task early, as well as regularly.

- Write down your understanding of what the task is asking you to do

- Write down what concepts/topics/areas might be useful for the task

- Make notes outlining possible plans of attack for the task

- Add to the notes as soon as new thoughts come to mind

- Think about problems or advantages with the plans. Focus on the most promising

- Review and revise the notes at least every couple of days

If you start doing this early enough, investments of a few minutes per day can pay off handsomely.

6. Summary/Conclusion

Here, at the end of LS3, we see that a complete concept pipeline looks like this:

The complete list of steps/stages is:

| Learning Stage | Pipeline Step |

|---|---|

| LS1 | 1 - Identify the next concept |

| LS1 | 2 - Understand the concept |

| LS2 | 3 - Decompose the concept into a set of facts |

| LS2 | 4 - Memorize the set of facts |

| LS2 | 5 - Integrate the memorized facts into a holistic concept |

| LS3 | 6 - Apply the concept(s) |

Each step builds on the previous one. Doing well at each step makes doing well in the next one much easier. Doing poorly at any step makes doing well in the later ones much harder, if not impossible.

Note that the new step here - step 6, the last step - is the only one that speaks of concepts, in plural. In LS3, you will need to work not just with individual concepts, but at the level of topics, or areas - sets of concepts. So your overall understanding of the subject, your Knowledge Model representing it, will ultimately, eventually, mirror the structure of the subject. This is why it is so important to identify, and keep track of, the subject's structure from the outset.

This was a long article, at least as internet articles go. You will not absorb all of this in a single reading. You will not execute this process flawlessly the first time you try it. But as you apply it repeatedly, with each new concept, with each new subject, the process will get easier, faster, more effective. It will become automatic.

You will have learned how to learn.

Once you have gotten the hang of studying with the Learning Stages, the next important thing to understand is that each Learning Stage requires different kinds of instructional sources, and each Learning Stage benefits from different study techniques.

Those articles are not ready yet. But you can get an idea of what they will look like in our guide to Programming Language Learning Stages.

Notes:

- 1 - Actually, you have to convert the facts into questions. But that's relatively easy.↵

- 2 - Even more precisely, Integration never really ends. It is potentially a life-long process, in the case of concepts that you continue to work with beyond the class in which you first learn them. You will continually expand and refine your understanding of them, though at a much slower pace than you do in LS2, or in LS3.↵

Learn More

- How Students Learn - Learning Stages - an introduction to the Learning Stages

- Programming language Learning Stages - how to learn a programming language (or any other technology tool)

- Choosing Instructional Sources for Each Learning Stage - (coming soon)

- Choosing Study Techniques for Each Learning Stage - (coming soon)

- A Teacher's Guide to Understanding the Learning Stages - (coming soon)

- Understanding Knowledge Models - (coming soon)

As you may expect, we here at SRSoterica understand that spaced repetition (SRS) is the most effective technique for LS2 (Absorption) learning. There is a substantial and growing body of research to support that claim.